Brimstone Alumina Hype

Brimstone’s Alumina Story: A Game-Changer or Just Another Hype Cycle?

Another hype piece written by an investor in Brimstone, DCVC, highlighting the company’s recent pivot away from decarbonizing cement and toward whatever terminal form of optimism this is, involving the alumina industry. I assume this move comes as the Trump administration promises to cancel anything climate, and Brimstone feels their exorbitant $189M federal funding is vulnerable to cancellation on a whim if their project looks too “green.” Hence the pivot to strategic national supply chain for alumina.

Why do I feel the need to comment on this? I think it’s the blend of arrogance and lack of acknowledgment of similar past efforts that bothers me. A blend of savior complex and beginner mindset. Let’s get into specifics:

From the article:

Alumina is the precursor to aluminum, a material essential to energy, defense, transportation, and manufacturing. Yet the U.S. remains heavily dependent on imports of alumina, primarily from China, as well as on bauxite, the primary source of alumina.

It’s true that aluminum is critical, and the U.S. remains heavily reliant on foreign sources for its raw materials. Diversifying domestic supply is not just about economics but national security as well. Agreed. However, alternatives to bauxite-based alumina production have been explored for decades with limited commercial success.

Having already developed the world’s first zero-carbon portland cement, DCVC portfolio company Brimstone has devised a way to produce smelter-grade alumina without relying on bauxite. The company’s proprietary “Rock Refinery” approach unlocks two essential materials—cement and alumina—from a single abundant feedstock.

Notes:

Brimstone’s “Rock Refinery” approach is a fun Silicon Valley-esque branding tool and not much more than that. Why not use the actual industry terms: mining and metallurgy? There is really nothing new here, and there are many existing “rock refineries”: mines, smelters, etc. It’s a nothing term.

It’s kind of a nice idea to extract both cement and alumina from a single feedstock. However, I’d like to see more details on the energy and material flows. Many “breakthrough” industrial processes look promising on paper but fall apart when faced with the harsh realities of large-scale processing, logistics, and market acceptance.

The goal of reshoring aluminum production has been explored to death in the past, such as processing coal fly ash, which was often free, higher in aluminum content, and easier to process than basalt and similar rocks. Alumina from fly ash was also proposed in conjunction with cement production as early as 1977, maybe earlier? Also, the challenge isn’t just “is it technically possible” but cost-effectiveness at scale wins every time.

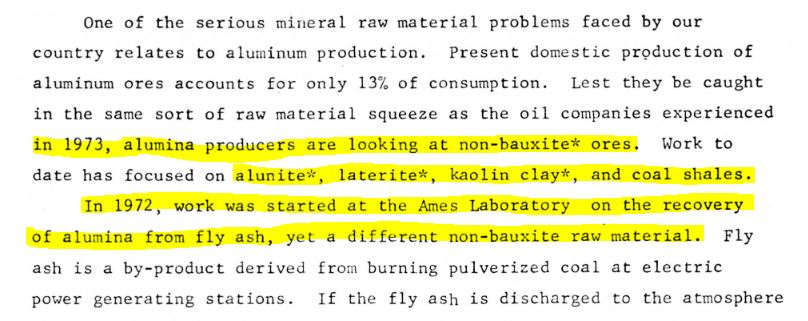

As you’ll note in this image from a 1977 Ames Laboratory report “Alumina from Fly Ash,” there are many better domestic alumina mineral sources in the “uneconomic” category before resorting to Brimstone’s rock choice of basalt (which they want for the small amount of calcium in it). For example, relatively pure kaolinite clay has about 30-40% alumina content vs. basalt at 10-15%. That’s a big deal for economics if alumina is actually the goal. I’m not sure it’s such a win to try and make both cement and alumina at the same time from common silicate minerals…

Brimstone’s technology not only extracts alumina from calcium silicate rocks, which make up a significant share of the Earth’s crust, but it also avoids the energy-intensive Bayer process used for refining bauxite.

Avoiding the Bayer process is an interesting proposition, given its high energy consumption and red mud waste problem. However, the Bayer process has endured for a reason—it remains the most cost-effective and scalable method despite its downsides. It’s just so cheap to dig up alumina-rich material and ship it around the world to places with cheap energy/electricity. An unfortunate reality is that having a big red mud tailings facility is not actually a barrier to operation in many parts of the world. I’d be curious to see a life-cycle analysis comparing Brimstone’s process to the traditional method in terms of energy inputs, emissions, and byproducts. I expect their models really need the centralized megaplant to get close to economic numbers. Can they survive as a company (paying about 70 people!) long enough to get to that scale?

Moreover, the company’s approach will require no green premium at full industrial scale—their alumina, cement, and supplementary cementitious materials (SCM) will sell at market price while delivering superior economics to conventional processes.

“No green premium” is a bold claim, especially from a company that has yet to build its first pilot plant. We’ll get into the hopium-fueled economics of Brimstone’s process another time, but suffice it to say that there is really no evidence that this will be achievable. Complicating matters is that they will need to succeed at about four difficult heavy industries just to stay in business: cement, alumina, SCMs, excess calcium, magnesium, and iron as carbon sinks?

Brimstone’s alumina announcement comes at a critical moment. Global supply chains face mounting pressures, and U.S. policymakers increasingly recognize the strategic imperative of domestic production capacity for essential materials.

The timing is definitely strategic. With growing geopolitical tensions and the U.S. determined to increase its cost of importing goods (via tariffs on aluminum), any viable domestic alternative to Chinese alumina may get serious attention. That said, political and financial support does not guarantee technical or commercial viability—just look at the history of government-backed materials startups that never scaled up. I’ll also say that the rocks Brimstone aims to mine only contain about 10-15% alumina at most—maybe they are realizing that this would be more economic to produce than their cementitious endeavor (but that’s not saying much!).

Brimstone’s vision has already earned substantial federal support, with the Department of Energy having selected Brimstone for up to $189 million in funding for its first commercial demonstration plant.

Many energy and materials startups have received substantial funding only to hit insurmountable technical or economic roadblocks. The key question remains: Can Brimstone deliver a fully integrated, cost-competitive process at commercial scale? By their own admission, this is a whack of money, but far from enough to even get their demo plant built.

Final Thoughts:

The idea of co-producing alumina and cement from non-bauxite sources is intriguing, especially if it avoids the environmental downsides of existing processes. However, industrial materials breakthroughs are notoriously difficult to commercialize, so doing a few at once is truly difficult. Until we see operational data from even a pilot plant, cautious optimism seems the right approach.

Does this sound like the future of materials processing to you, or are we in a clean-tech hype cycle for these companies trying to raise capital this year?